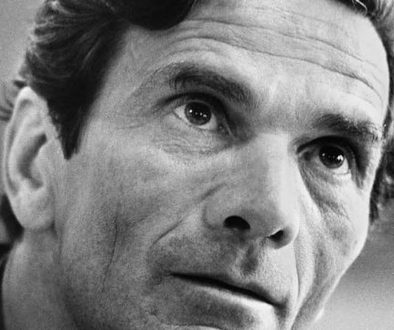

“Louisa May Alcott”-poetessa e scrittrice di Beatrice Masini-Biblioteca DEA SABINA

Biblioteca DEA SABINA

“Louisa May Alcott”-poetessa e scrittrice

di Beatrice Masini

Giulio Perrone Editore -Roma

Descrizione-Di Louisa May Alcott si sa quel poco che le alette dei suoi romanzi ci concedono: che è l’autrice di Piccole donne e dei suoi seguiti, e che ha conosciuto in vita un successo destinato a durare come autrice di libri per ragazzi, anzi, per ragazze. Ma come è arrivata a scrivere la storia di una famiglia che assomiglia tanto alla sua? E da quale vena narrativa sgorgano le altre sue opere, decine e decine di racconti gotici “di sangue e tuono”, romanzi audaci e romanzi commerciali, qualcuno firmato, altri pubblicati anonimi o sotto pseudonimo?

Ripercorrere la sua vita è viaggiare in un mondo complicato, ricco di opportunità per le giovani donne ma sempre pronto a richiamarle all’ordine, per scoprire una ragazza fuori moda che sognava di essere se stessa ed è diventata “una sorta di tata letteraria che produce pappetta morale per i piccoli”. Una ragazza forte per forza, cresciuta in una casa povera di oggetti e ricca di ideali, diventata una donna lavoratrice per pagare conti e debiti altrui. In questo la storia di Alcott assomiglia a quella di tante altre scrittrici celebri, sempre in bilico tra necessità e libertà, e qualche volta si intreccia con la loro.

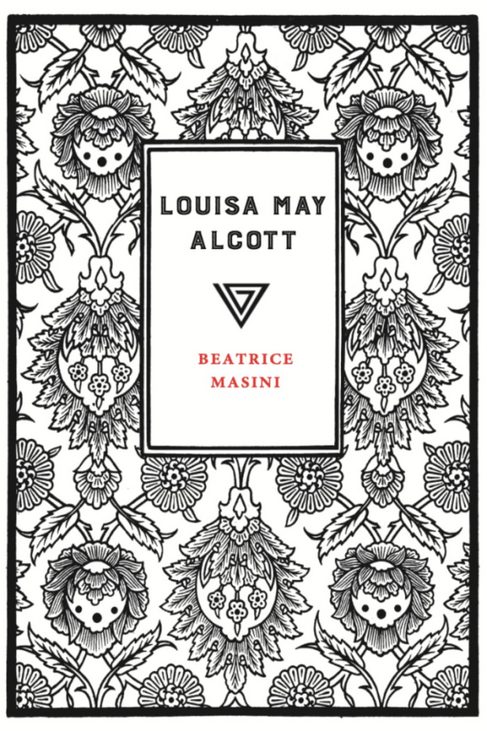

Louisa May Alcott (/ˈɔːlkət, –kɒt/; November 29, 1832 – March 6, 1888) was an American novelist, short story writer, and poet best known for writing the novel Little Women (1868) and its sequels Good Wives (1869), Little Men (1871), and Jo’s Boys (1886). Raised in New England by her transcendentalist parents, Abigail May and Amos Bronson Alcott, she grew up among many well-known intellectuals of the day, including Margaret Fuller, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Nathaniel Hawthorne, and Henry David Thoreau. Encouraged by her family, Louisa began writing from an early age.

Louisa’s family experienced financial hardship, and while Louisa took on various jobs to help support the family from an early age, she also sought to earn money by writing. In the 1860s she began to achieve critical success for her writing with the publication of Hospital Sketches, a book based on her service as a nurse in the American Civil War. Early in her career, she sometimes used pen names such as A. M. Barnard, under which she wrote lurid short stories and sensation novels for adults. Little Women was one of her first successful novels and has been adapted for film and television. It is loosely based on Louisa’s childhood experiences with her three sisters, Abigail May Alcott Nieriker, Elizabeth Sewall Alcott, and Anna Alcott Pratt.

Louisa was an abolitionist and a feminist and remained unmarried throughout her life. She also spent her life active in reform movements such as temperance and women’s suffrage. During the last eight years of her life she raised the daughter of her deceased sister. She died from a stroke in Boston on March 6, 1888, just two days after her father’s death and was buried in Sleepy Hollow Cemetery. Louisa May Alcott has been the subject of numerous biographies, novels, and a documentary, and has influenced other writers and public figures such as Ursula K. Le Guin and Theodore Roosevelt.

Early life

Birth and early childhood

Louisa May Alcott was born on November 29, 1832, in Germantown,[1] now part of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Her parents were transcendentalist and educator Amos Bronson Alcott and social worker Abigail May.[2] Louisa was the second of four daughters, with Anna as the eldest and Elizabeth and May as the youngest.[3] Louisa was named after her mother’s sister, Louisa May Greele, who had died four years earlier.[4] After Louisa’s birth, Bronson kept a record of her development, noting her strong will,[5] which she may have inherited from her mother’s May side of the family.[6] He described her as “fit for the scuffle of things”.[7]

The family moved to Boston in 1834,[8] where Louisa’s father established the experimental Temple School[9] and met with other transcendentalists such as Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau.[10] Bronson participated in child-care but often failed to provide income, creating conflict in the family.[11] At home and in school he taught morals and improvement, while Abigail emphasized imagination and supported Alcott’s writing at home.[12] Writing helped her handle her emotions.[13] Louisa was often tended by her father’s friend Elizabeth Peabody,[14] and later she frequently visited Temple School during the day.[15]

Louisa kept a journal from an early age. Bronson and Abigail often read it and left short messages for her on her pillow.[16] She was a tomboy who preferred boys’ games[17] and preferred to be friends with boys or other tomboys.[18] She wanted to play sports with the boys at school but was not allowed to.[19]

Alcott was primarily educated by her father, who established a strict schedule and believed in “the sweetness of self-denial.”[20] When Louisa was still too young to attend school, Bronson taught her the alphabet by forming the letter shapes with his body and having her repeat their names.[21] For a time she was educated by Sophia Foord,[22] whom she would later eulogize.[23] She was also instructed in biology and Native American history by Thoreau, who was a naturalist,[24] while Emerson mentored her in literature.[25] Louisa had a particular fondness for Thoreau and Emerson; as a young girl, they were both “sources of romantic fantasies for her.”[26] Her favorite authors included Harriet Beecher Stowe, Sir Walter Scott, Fredericka Bremer, Thomas Carlyle, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Goethe, and John Milton, Friedrich Schiller, and Germaine de Staele.[27]

Hosmer Cottage

| External videos | |

|---|---|

In 1840, after several setbacks with Temple School and a brief stay in Scituate,[28] the Alcotts moved to Hosmer Cottage in Concord.[29] Emerson, who had convinced Bronson to move his family to Concord, paid rent for the family,[30] who were often in need of financial help.[31] While living there, Alcott and her sisters befriended the Hosmer, Goodwin, Emerson, Hawthorne, and Channing children, who lived nearby.[32] The Hosmer and Alcott children put on plays and often included other children.[33] Louisa and Anna also attended school at the Concord Academy, though for a time Louisa attended a school for younger children held at the Emerson house.[34] At eight years-old, Louisa wrote her first poem, “To the First Robin”. When she showed the poem to her mother, Abigail was pleased.[35]

In October 1842 Bronson returned from a visit to schools in England[36] and brought Charles Lane and Henry Wright with him[37] to live at Hosmer Cottage, while Bronson and Lane made plans to establish a “New Eden”.[38] The children’s education was undertaken by Lane, who implemented a strict schedule. Louisa disliked Lane and found the new living arrangements difficult.[39]

Fruitlands and Hillside

In 1843 Bronson and Lane established Fruitlands, a utopian community,[40] in Harvard, Massachusetts, where the family were to live.[41] Louisa later described these early years in a newspaper sketch titled “Transcendental Wild Oats”, reprinted in Silver Pitchers (1876), which relates the family’s experiment in “plain living and high thinking” at Fruitlands.[42] There, Louisa enjoyed running outdoors and found happiness in writing poetry about her family, elves, and spirits. She later reflected with distaste on the amount of work she had to do outside of her lessons.[43] She also enjoyed playing with Lane’s son William and often put on fairy-tale plays or performances of Charles Dickens‘s stories.[44] She read works by Dickens, Plutarch, Lord Byron, Maria Edgeworth, and Oliver Goldsmith.[45]

During the demise of Fruitlands, the Alcotts discussed whether or not the family should separate. Louisa recorded this in her journal and expressed her unhappiness should they separate.[46] After the collapse of Fruitlands in early 1844, the family rented in nearby Still River,[47] where Louisa attended public school and wrote and directed plays that her sisters and friends performed.[48]

In April 1845 the family returned to Concord, where they bought a home they called Hillside with money Abigail inherited from her father.[49] Here, Louisa and her sister Anna attended a school run by John Hosmer after a period of home education.[50] The family again lived near the Emersons, and Louisa was granted open access to the Emerson library, where she read Carlyle, Dante, Shakespeare, and Goethe.[51] In the summer of 1848 sixteen-year-old Louisa opened a school of twenty students in a barn near Hillside. Her students consisted of the Emerson, Channing, and Alcott children.[52]

The two oldest Alcott girls continued acting in plays written by Louisa. While Anna preferred portraying calm characters, Louisa preferred the roles of villains, knights, and sorcerers. These plays later inspired Comic Tragedies (1893).[53] The family struggled without income beyond the girls’ sewing and teaching. Eventually, some friends arranged a job for Abigail[54] and three years after moving into Hillside, the family moved to Boston. Hillside was sold to Nathaniel Hawthorne in 1852.[55] Louisa described the three years she spent at Concord as a child as the “happiest of her life.”[56]

Boston

When the Alcott family moved to South End, Boston in 1848,[57] Louisa had work as a teacher, seamstress, governess, domestic helper, and laundress, to earn money for the family.[58] Together, Louisa and her sister taught a school in Boston,[59] though Louisa disliked teaching.[60] Her sisters also supported the family by working as seamstresses, while their mother took on social work among the Irish immigrants. Elizabeth and May were able to attend public school, though Elizabeth later left school to undertake the housekeeping.[61] Due to financial pressures, writing became a creative and emotional outlet for Louisa.[62] In 1849 she created a family newspaper, the Olive Leaf, named after the local Olive Branch. The family newspaper included stories, poems, articles, and housekeeping advice.[63] It was later renamed to The Portfolio.[64] She also wrote her first novel, The Inheritance, which was published posthumously and based on Jane Eyre.[65] Louisa, who was driven to escape poverty, wrote, “I wish I was rich, I was good, and we were all a happy family this day.”[66]

Early adulthood

Life in Dedham

Abigail ran an intelligence office to help the destitute find employment.[67] When James Richardson came to Abigail in the winter of 1851 seeking a companion for his frail sister and elderly father who would also be willing to do light housekeeping,[68] Louisa volunteered to serve in the house filled with books, music, artwork, and good company on Highland Avenue.[69] Louisa may have imagined the experience as something akin to being a heroine in a Gothic novel, as Richardson described their home in a letter as stately but decrepit.[69]

Richardson’s sister, Elizabeth, was 40 years old and suffered from neuralgia.[70] She was shy and did not seem to have much use for Louisa.[69] Instead, Richardson spent hours reading her poetry and sharing his philosophical ideas with her.[71] She reminded Richardson that she was hired to be Elizabeth’s companion and expressed that she was tired of listening to his “philosophical, metaphysical, and sentimental rubbish.”[69] Richardson’s response was to assign her more laborious duties, including chopping wood, scrubbing the floors, shoveling snow, drawing water from the well, and blacking his boots.[72]

Louisa quit after seven weeks, when neither of the two girls her mother sent to replace her decided to take the job.[69] As she walked from Richardson’s home to Dedham station, she opened the envelope he handed her with her pay.[69] One account states that she was so unsatisfied with the four dollars she found inside that she mailed the money back to him in contempt.[69] Another account states that Bronson may have returned the money himself and rebuked Richardson.[73] Louisa later wrote a slightly fictionalized account of her time in Dedham titled “How I Went Into Service”, which she submitted to Boston publisher James T. Fields.[74] Fields rejected the piece, telling Louisa that she had no future as a writer.[74]

Autrice Beatrice Masini è nata a Milano, dove lavora nell’editoria.Giornalista al Giornale e poi alla Voce, editor, traduttrice, scrive per bambini e per adulti. I suoi libri per ragazzi (albi, racconti, romanzi) sono tradotti in una ventina di lingue. Bambini nel bosco (Fanucci, 2010) è stato il primo libro per ragazzi ad essere selezionato per il Premio Strega. Con Tentativi di botanica degli affetti (Bompiani, 2013) ha vinto il premio Selezione Campiello, il premio Viadana, il premio Alessandro Manzoni.